College Chemistry Professors: The Hard Work Behind the Position

Becoming a college chemistry professor demands extensive education, intense research training, and significant perseverance. The journey spans a typical academic path including a bachelor’s degree, a PhD, multiple postdoctoral positions, teaching experience, and navigating a fiercely competitive job market. Passion for the subject and resilience shape success as much as academic credentials.

Academic Career Path and Educational Requirements

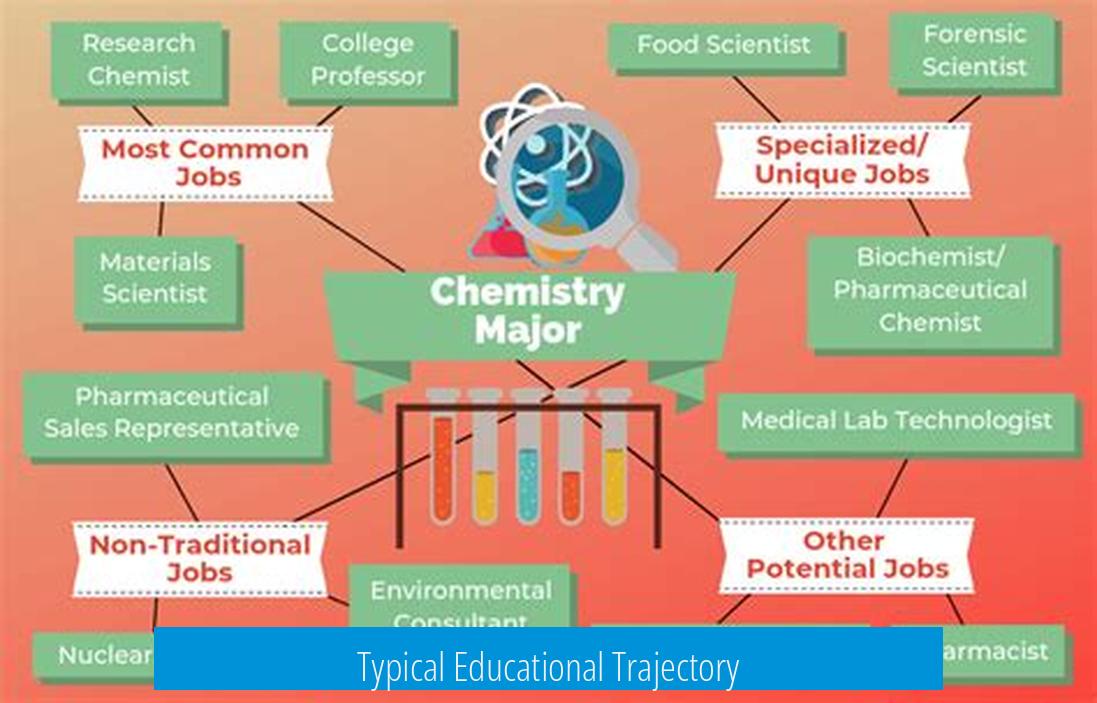

Typical Educational Trajectory

The path to becoming a college chemistry professor generally demands several educational stages. Most candidates complete a bachelor’s degree in chemistry or a related field, usually taking four years. This is followed by a PhD program that lasts 4 to 7 years. After earning a PhD, candidates often undertake one or two postdoctoral positions, each lasting about 2 years. These postdoctoral stints provide focused research experience critical for academic competitiveness.

After postdocs, candidates apply for tenure-track assistant professor roles, which begin the formal professorship career. Reaching tenured professor status takes additional years of research, teaching, and service to the institution.

Necessity of PhD and Postdoctoral Experience

A PhD is a non-negotiable credential for full-time professorships at four-year colleges and universities, especially at large state or private research institutions. Community colleges may accept candidates with a master’s degree, but research institutions require deep expertise demonstrated by doctoral research.

Completing postdoctoral research is also basically required except in rare, exceptional cases. The postdoc phase sharpens research skills, builds publication records, and establishes professional networks. Without these qualifications, candidates struggle to compete with the large pool of PhD holders applying for limited faculty positions.

Timing and Flexibility in Choosing Academia

Aspiring professors decide on the academic track at different stages. Some decide as early as their sophomore undergraduate years after narrowing career goals. Others only commit after completing their PhDs once they understand the demands and opportunities in academia. Regardless, cultivating a strong reputation during the PhD and postdoc years is essential for later job prospects.

Financing Graduate Education

PhD programs in chemistry typically provide stipends or salaries sufficient to cover living expenses, often above $20,000 annually. Additional fellowships or scholarships can increase earnings during graduate study. This financial support enables students to focus on research and coursework without accruing significant debt.

Workload and Effort During Training

Research Intensity and Long Hours

The training phase involves substantial time commitments. Many report working 70-hour weeks or more throughout graduate school and postdoc tenures. Early research often starts during undergraduate studies. A successful candidate may accumulate dozens of published papers by the time they enter a faculty position.

Research time varies with career stage. Some professors spend years primarily writing grant proposals and managing laboratories rather than hands-on lab work. The shift from bench chemistry to administrative duties marks a transition in daily tasks.

Developing Skills Beyond Chemistry Benchwork

The role demands more than chemical expertise. A professor runs a small research business by securing funding, publishing findings, mentoring students, and collaborating with industry or other institutions. The skill set includes grant writing, managing teams, budgeting, and strategic planning, which are rarely taught explicitly during graduate training but are essential to academic success.

Teaching Experience and Preparation

Teaching as an Added Responsibility

Teaching is a core responsibility for professors. Some graduate students gain teaching experience as teaching assistants or instructors for general chemistry, analytical chemistry, or graduate courses. While graduate school research may not require teaching, many find that teaching assignments provide valuable experience and extra income.

Importance of Teaching Preparation

Graduate students should seek opportunities to develop teaching skills through formal training programs or substitute teaching roles. Prior teaching experience can enhance a candidate’s portfolio and ease the transition to faculty roles that emphasize instructional duties.

Teaching Focus Varies by Institution

The emphasis on teaching versus research shifts depending on the institution type. Large state universities typically prioritize research output and grant acquisition, with teaching as a secondary duty. Private or liberal arts colleges often expect more teaching commitment and value high-quality instruction.

Community colleges place even stronger emphasis on teaching, frequently requiring only a master’s degree for faculty roles. Understanding the institutional culture helps tailor one’s preparation and career goals.

Job Market Difficulty and Competition

High Competition for Limited Positions

The academic job market in chemistry is highly competitive. Individual faculty openings commonly attract hundreds, sometimes over 700, applicants. Candidates compete on research records, teaching experience, and potential for securing funding.

Passion for chemistry and academia emerges as a key factor for survival and success. The workload and competition are so intense that candidates who do not deeply enjoy the work struggle to maintain the necessary commitment.

Geographic Mobility and Early Career Challenges

Landing the first academic job is the most difficult hurdle. Candidates are often unknown and must convince committees of their potential despite limited independent experience. Greater geographic flexibility increases chances of securing a position. Post initial employment, switching jobs can become easier as candidates gain experience and reputation.

Frequent moves for postdocs and early faculty appointments are common and require personal adaptation, despite institutions often covering moving expenses. Multiple relocations present logistical and social challenges.

Academic Job Types and Titles

Non-Tenure Track Roles

Positions such as research associates or associate research professors exist but are typically funded through research grants and do not offer tenure. These roles can offer greater research freedom without administrative or teaching pressures but lack job security and departmental influence.

Visiting Professorships

Visiting professorships fill temporary teaching or research needs during sabbaticals or administrative leaves. Candidates may enjoy travel and diverse experiences, often coupled with fewer administrative burdens. Visiting roles suit those who prioritize enjoyment of academic life over permanent status or salary stability.

Personal Reflections on Academic Life

Admiration and Frustrations

Academics find joy in intellectual freedom and mentorship but report frustrations with university administration and grant dependency. The pressure to secure funding dominates many professors’ time, and teaching may be seen as an additional burden in research-heavy environments.

Transition from Laboratory Work to Managerial Roles

Professors typically reduce direct bench work as their careers progress, focusing instead on writing, strategy, mentoring, and leadership. Some miss hands-on experiments; others adapt readily. Effective professors combine scientific expertise with managerial skills.

Geographic and Institutional Influences

Differences in Job Markets Between Countries

In the UK, academic routes share similarities with the US but may involve different timing and institutional prestige levels. For example, landing a tenure-track position often requires experience at top universities and solid publication records. The UK market can be narrower, increasing competition.

Influence of U.S. States and Institutions

Career paths may vary by region and institution. Professors frequently move among universities in different states to find faculty openings or visiting roles. Institutional cultures vary widely, offering diverse opportunities in research, teaching, or administrative roles.

Key Takeaways

- Becoming a chemistry professor requires a minimum of 8-13 years of post-bachelor education including PhD and postdocs.

- A PhD and postdoctoral research are essential to compete for tenure-track faculty roles at research universities.

- Graduate training involves intensive research, often 60-70 hour weeks, and building a strong publication record.

- Teaching experience and skill development augment research credentials and are crucial depending on institution type.

- The academic job market is fiercely competitive with hundreds of applicants for few positions.

- Geographic flexibility improves job prospects and navigating early career moves is challenging.

- Academic roles vary from tenure-track, non-tenure research positions, to visiting professorships, each with pros and cons.

- Professors balance research, teaching, mentoring, and grant writing, often stepping away from bench work.

- Passion, persistence, and adaptability are vital for enduring the demands of an academic career in chemistry.

College Chemistry Professors: How Hard Did You Have to Work to Achieve Your Position?

Becoming a college chemistry professor is no walk in the park — it demands YEARS of relentless hard work, dedication, and passion. From the initial undergraduate degree all the way to holding a coveted tenured position, the journey is intense, competitive, and layered with unique challenges. So, how hard did you have to work? Let’s break it down.

First off, if you want a seat at the college chemistry professor table, there’s no shortcut around education. Almost everyone starts with a Bachelor’s degree, typically a four-year commitment. But that’s just the warm-up.

The Educational Climb: Bachelors, PhD, and Postdoc

After the Bachelor’s, the real grit begins with a PhD, which can stretch anywhere from four to seven years. Many might cringe at that number, but it’s the price of entry. And wait—there’s more. Exactly like a plot twist in a TV series, those aiming for tenure at well-known universities usually tack on 1 to 2 postdoctoral research periods, each lasting around two years. This postdoc phase is essential—it’s the prime time to sharpen research skills, publish critical papers, and build a reputation.

*“I got my Bachelor’s, then a PhD, then a 3-year postdoc before landing my current assistant professor position,”* shares one professor’s timeline.

We’re talking about a decade or more of grinding through research, lab work, and publications before even hitting the assistant professor role. The workload? Often 70 hours a week during graduate school and postdocs. Think long days filled with experiments and paper writing, running on caffeine and determination. Most chemistry grad students and postdocs become no strangers to late nights in the lab.

PhD and Postdoc: The Non-Negotiables

One cannot emphasize enough: a PhD is absolutely required to land a full-time chemistry professor gig at most universities. Miss this step, and you’ll struggle to be a competitive candidate among hundreds of PhD holders. Exceptions are rare, mostly at community colleges where a master’s degree often suffices, but for big state or private universities—the PhD is your golden ticket.

And the postdoc? It’s usually a must unless you’re a rare prodigy. Postdoctoral positions help build that crucial record of published work and independent research skills. It’s a proving ground before the academic job market lets you even peek in the door.

When to Decide on Academia?

Some choose their academic path early. For example, in sophomore year, one might drop the pre-med track and jump into chemistry, setting the course for tenure. Others hang in limbo until PhD graduation, deciding late but still able to turn it into a success if they build a solid professional rep during their doctoral studies. The message? Whether early or late, commitment, and cultivation of skills and networks are what matter.

Graduate School Funding and Fellowships

If you fear burning through life savings during your PhD, here’s some relief: most respectable programs offer stipends (roughly $20,000 a year) to support you. Snagging a fellowship can boost this, essentially a financial nod toward your promise as a scientist.

The Post-Training Reality: Research, Teaching, and New Skills

Once you secure a position, your life takes a new shape. Early years are research-heavy—churning out papers, attending conferences, and constantly pushing the boundaries of chemistry. Many professors report spending little hands-on time at the bench later on, pivoting instead to writing, managing, and mentoring roles.

“I spend all my time writing now,” one professor admits, “I don’t miss benchwork — I was never a magic-hand chemist.” That’s a fascinating shift, right? The skillset evolves from pure experimental science to managing a small, research-driven business. Professors sell ideas, chasing grants and company collaborations, translating their science into money and credibility.

Early years can feel like a grind, but one key piece of advice from seasoned pros is clear: hustle hard in research but *also* embrace teaching opportunities. Being a TA, substitute teaching, or joining programs to learn better teaching methods can pay dividends. After all, you’ll be expected to teach, often courses like general chemistry, analytical chemistry, or specialized instrumental analysis. Some universities pay extra for teaching beyond research duties, a nice bonus for those juggling both.

Teaching Emphasis Varies by Institution

The role you play as a chemistry professor can depend heavily on where you teach. At big, research-focused universities, teaching might be an afterthought, sometimes even an annoyance. These places expect professors to excel at publishing and grant writing. Smaller colleges and private institutions tend to value teaching more, giving professors more opportunity (and obligation) to engage directly with students. Community colleges usually require only a master’s degree, with primary focus on teaching rather than research.

The Job Market: Fierce Competition and First-Job Challenges

Be prepared to face a crowded field. One chemistry professor noted an interview with 700 applicants for a single position. Yes, you read that right. When there are hundreds competing for a handful of jobs, passion isn’t optional—it’s a survival tool.

Landing your first job is notably tricky. Institutions tend to prefer candidates with experience, so recent PhDs often face tough odds. Flexibility helps: willingness to move geographically broadens your options drastically. Universities usually cover moving costs, thankfully, but packing boxes repeatedly remains a mixed blessing.

After the first appointment, finding new positions typically becomes easier. Academic chairs remember good candidates; once you’re “in the club,” life improves—though the job moves can still be a hassle.

Tenure-Track vs. Visiting and Non-Tenure Positions

Not every academic position looks the same. Some professors start as research associates, paid directly from their grant money rather than the university’s budget. This status can offer freedom, keeping them above the fray of departmental politics.

Visiting professorships offer another flavor. One seasoned academic describes enjoying the lifestyle of visiting roles, appreciating the chance to work across multiple institutions, avoiding ruts, and often having summers off. Financial concerns take a backseat at this career stage, making passion the primary driver.

Personal Reflections: Balancing Frustration and Fulfillment

Academic life isn’t all sunshine and stardust. Many professors face frustration with bureaucratic red tape and administrative overhead. One observed, “I spent seven years increasingly frustrated by turgid administration before retiring.” For some, time spent chasing grants overshadows the joy of teaching, turning it into a chore.

But despite occasionally feeling worn down, many professors swear it’s the best job on Earth. The ability to dive deep into intellectual puzzles, mentor fresh minds, and experiment creatively can energize and inspire. Teaching the way they always hoped to be taught is a recurring reward that keeps them coming back.

Global and Geographic Variations: UK vs US Academic Careers

The path to professorship can differ by country. For instance, a UK chemist might start with an MChem, jump into a PhD where they become their advisor’s first graduate student, then proceed through postdocs at top labs. Landing a tenure-track job at 32 after only 5 postdocs typifies the arduous climb internationally.

In the US, professors often move among universities in various states, adapting to different institutional cultures. Interview rounds, relocations, and contracts form the backdrop to academic life. Mobility is part of the package.

So, How Hard Is It, Really?

In a word: HARD. The academic track for a chemistry professor spans 10+ years of intense study, overwork, and competition. It demands constant honing of research and teaching skills, adaptability, and frequent mobility. You need more than smarts—you need passion, stamina, and a thick skin.

But here’s the kicker: those who love chemistry and teaching say it’s worth every grueling hour. After all, how many jobs let you solve intriguing puzzles, lead eager students, and explore the frontiers of science all at once?

Final Takeaways for Aspiring Chemistry Professors

- Get your PhD. No exceptions. It’s the passport to competing in academia.

- Embrace postdocs. They are your proving ground to build research credentials and publish.

- Work hard and long hours, especially during training. 70+ hour weeks are typical in grad school and postdocs.

- Don’t shy from teaching. Seek out TA roles and trainings early to build confidence and resume strength.

- Stay flexible geographically. You may have to move far and often to find positions.

- Learn managerial and grant-writing skills. Being a professor means running a small research business, selling ideas constantly.

- Keep your passion alive. The competition is fierce. Loving your work full-throttle helps you endure.

To put it simply: being a college chemistry professor means playing the long game. It is demanding, competitive, and at times maddening. But with persistence and passion, it becomes a uniquely fulfilling career. Ready to roll up your sleeves?

Leave a Comment