Understanding Hydrated Lime and Quicklime

Hydrated lime and quicklime are two chemical forms derived from calcium compounds, mainly calcium carbonate (chalk). Quicklime is calcium oxide (CaO), produced by heating calcium carbonate intensely. Hydrated lime, calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2), results from adding water to quicklime. Both play vital roles in industrial and environmental processes.

Chemical Transformation from Chalk to Lime Forms

- Chalk (Calcium Carbonate): The raw material, calcium carbonate (CaCO3), commonly found as chalk.

- Production of Quicklime (Calcium Oxide): Heating chalk in a hot flame drives off carbon dioxide, yielding quicklime (CaO).

- Conversion to Hydrated Lime (Calcium Hydroxide): Adding water to quicklime—known as slaking—produces hydrated lime (Ca(OH)2) and releases heat.

- Reversion to Calcium Carbonate: When hydrated lime stands exposed to air, it absorbs carbon dioxide and gradually converts back to calcium carbonate.

- Garden Lime: Composed mainly of crushed chalk (calcium carbonate), used primarily for neutralizing soil acidity.

Properties and Uses of Hydrated Lime

Hydrated lime appears as a fine powder. It is typically mixed with water for use in various applications.

- Wastewater Treatment: Hydrated lime serves to raise pH and remove impurities in water treatment plants.

- Chemical Properties: It exhibits a high pH, making it strongly alkaline but less reactive than quicklime.

- Reactivity and Material Effects: Though it slowly corrodes metals, construction materials like wood used in treatment plants can remain intact for decades.

- Health Considerations: Repeated skin contact dries skin; inhaling dust over time harms lungs, esophagus, and microbiomes.

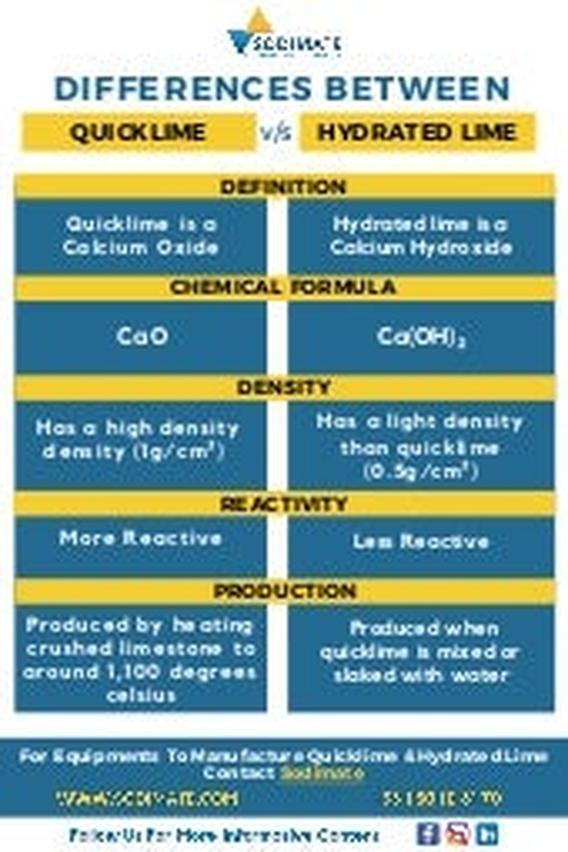

Comparison Table: Quicklime vs Hydrated Lime

| Property | Quicklime (CaO) | Hydrated Lime (Ca(OH)2) |

|---|---|---|

| Production | Roasting calcium carbonate at high heat | Adding water to quicklime (slaking) |

| Form | Solid, granular or lump | Powder |

| Reactivity | Highly reactive, generates heat upon hydration | Less reactive, more stable in use |

| Applications | Steelmaking, chemical synthesis | Water treatment, soil stabilization |

Key Takeaways

- Quicklime is calcium oxide made by heating chalk (calcium carbonate).

- Hydrated lime forms when water is added to quicklime, producing a powder used in water treatment.

- Both revert to calcium carbonate when exposed to air by absorbing carbon dioxide.

- Hydrated lime has a high pH, is less reactive than quicklime, but it can irritate skin and lungs on repeated exposure.

- Garden lime is crushed chalk; often confused with quicklime or hydrated lime but chemically different.

Trying to Understand Hydrated Lime and Quicklime: The Lime Puzzle Unwrapped

So, what exactly are hydrated lime and quicklime, and how do they relate to the humble chalk in your garden? Let’s unravel this lime mystery step-by-step. Whether you’re into chemistry, construction, or just curious about what’s ticking behind those chalky powders, this guide breaks down everything you need to know in a straightforward and engaging way.

From Chalk to Lime: A Chemical Journey

It all begins with chalk, known chemically as calcium carbonate. Think of chalk as the *raw ingredient* for lime products. Now imagine baking this chalk in a furnace at very high temperatures. This roasting action removes carbon dioxide, transforming chalk into something new—quicklime, or calcium oxide. This step is a classic example of turning a simple, natural material into a useful industrial product by changing its chemical structure.

But quicklime isn’t very user-friendly in its raw hot form. It needs to be “slaked” — no, that’s not a fancy dance move, but the addition of water. When water meets quicklime, it triggers a hot chemical reaction, producing hydrated lime (calcium hydroxide). This slaking generates plenty of heat, sometimes surprising those who try it without caution.

Interestingly, the saga doesn’t stop there. When hydrated lime is left standing exposed to air, it begins to absorb carbon dioxide. This action slowly transforms it back into calcium carbonate—the same as chalk! It’s like the lime is taking a full-circle trip, back where it began. This cycle highlights lime’s dynamic nature and its ability to adapt depending on environmental conditions.

Lastly, a quick shoutout to garden lime, which isn’t actually lime transformed by heat, but just crushed chalk, ready to neutralize acidic soil with its gentle calcium carbonate goodness.

Hydrated Lime: The Mild Mannered Hero

Hydrated lime arrives primarily as a fine powder. Typically, users mix this powder with water to activate its properties for various applications. One popular use is in wastewater treatment. Hydrated lime doesn’t just sit pretty—it plays a critical role in purifying water by adjusting the pH and facilitating contaminant removal.

Thanks to its relatively gentle reactivity, hydrated lime does not cause intense chemical reactions like quicklime might. This makes it safer to handle—in moderation, of course.

Be warned though: repeated exposure to hydrated lime can dry out your skin, so glove up if you’re working with it regularly. Inhaling its dust can cause irritation and damage to the lungs, esophagus, and even your microbiome. Safety gear isn’t just a suggestion here; it’s a must.

One remarkable feature of hydrated lime is its high pH level. This alkalinity helps it act as a disinfectant and neutralizer. It’s powerful enough to slowly erode metals, so materials like steel might eventually suffer. But here’s a fun fact from industry veterans: the wooden walls of plants exposed to hydrated lime for 30 years remain in good shape. Wood laughs in the face of lime’s caustic tendencies—at least for decades!

Why Does This Matter? Practical Takeaways

If you’re thinking “Okay, cool chemistry, but what about real-life uses?” Here’s why understanding hydrated lime and quicklime matters:

- Construction: Quicklime is essential in making mortar, plaster, and cement. Adding water to it gives workable hydrated lime, improving spreadability and strength.

- Environmental Work: Hydrated lime is a champion in treating wastewater, neutralizing acidic soils, and controlling odor in waste facilities.

- Gardening: Garden lime, which is crushed chalk, eases overly acidic soils and boosts plant growth.

Think of hydrated lime as the *gentler sibling* to the more intense quicklime—still powerful, but kinder and easier to manage in many applications.

Key Differences at a Glance

| Feature | Quicklime (Calcium Oxide) | Hydrated Lime (Calcium Hydroxide) |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Chalk roasted at high heat | Quicklime mixed with water (slaking) |

| Form | Solid, highly reactive | Powder, less reactive |

| Reaction to Water | Violent, produces heat | Stable mixable powder |

| Common Uses | Construction, chemical production | Wastewater treatment, soil amendment |

| Health Risks | Caustic, harmful on contact | Less hazardous but inhalation risks |

Wrapping It Up: What Should You Remember?

Hydrated lime and quicklime may seem like close relatives, but their roles and characteristics set them worlds apart. Understand them as different stages of chalk’s transformation journey. This knowledge helps workers in construction, agriculture, and environmental industries handle these materials safely and effectively.

Next time you see a sack labeled “hydrated lime” or “quicklime,” you’ll appreciate the fascinating chemistry and practical magic behind these powders. Don’t just toss them around—respect the heat, the pH, and the career path straight from chalk to lime and back again.

Want to play scientist in your own backyard? Remember, garden lime is gentle crushed chalk—safe for plants, easy on your hands, and a direct nod to the humble beginnings of quicklime and hydrated lime. Whether you’re a chemistry geek, a farmer, or a DIY builder, knowing your limestones adds layers to your skillset and keeps your projects lime-light worthy.

What is the difference between quicklime and hydrated lime?

Quicklime is calcium oxide made by roasting chalk. Hydrated lime is made by adding water to quicklime, a process called slaking. This produces calcium hydroxide and releases heat.

How does hydrated lime revert to chalk?

When exposed to air, hydrated lime absorbs carbon dioxide and converts back to calcium carbonate, which is similar to chalk.

Why is hydrated lime used in wastewater treatment?

Hydrated lime is added in powder form to water. It raises pH and helps neutralize acidic wastes without causing intense reactions.

Is hydrated lime safe to handle?

It can dry out skin with repeated exposure. Breathing it in multiple times may harm lungs, esophagus, and the microbiome.

How does hydrated lime affect metals and wood?

It slowly erodes metal, but wood exposed to hydrated lime can last many years without damage, as seen in long-running facilities.

Leave a Comment